Edith Keyser White '31, Teresa White Riddle ’68, M.Ed. ’76, and Alice White Parrish ’69

Edith Keyser was on the verge of graduating as part of the second-ever cohort of students to complete their degrees at UCLA’s new campus in Westwood. But there was this annoying “technicality” standing in her way: in 1931, the University had a physical education requirement, and Edith was just not very good at PE.

She found a solution, though: she would take folk dancing – that was something she could do, and it would satisfy the PE component of her education. Everything seemed on track until it turned out that folk dancing required physical contact with other students. This really shouldn’t have been a problem; there was no pandemic going on at that time, so touching another student did not pose a health risk. And, in fact, the only student affected by this aspect of the course was Edith: the other girls in the class would not hold her hand – because she was Black.

Edith did graduate. Whether the other girls relented or the instructor allowed her to participate with “social distancing” has been lost to history, but she was, indeed, part of the class of 1931, graduating with a B.A. in history, the first in a multi-generation UCLA family of extremely proud Bruins.

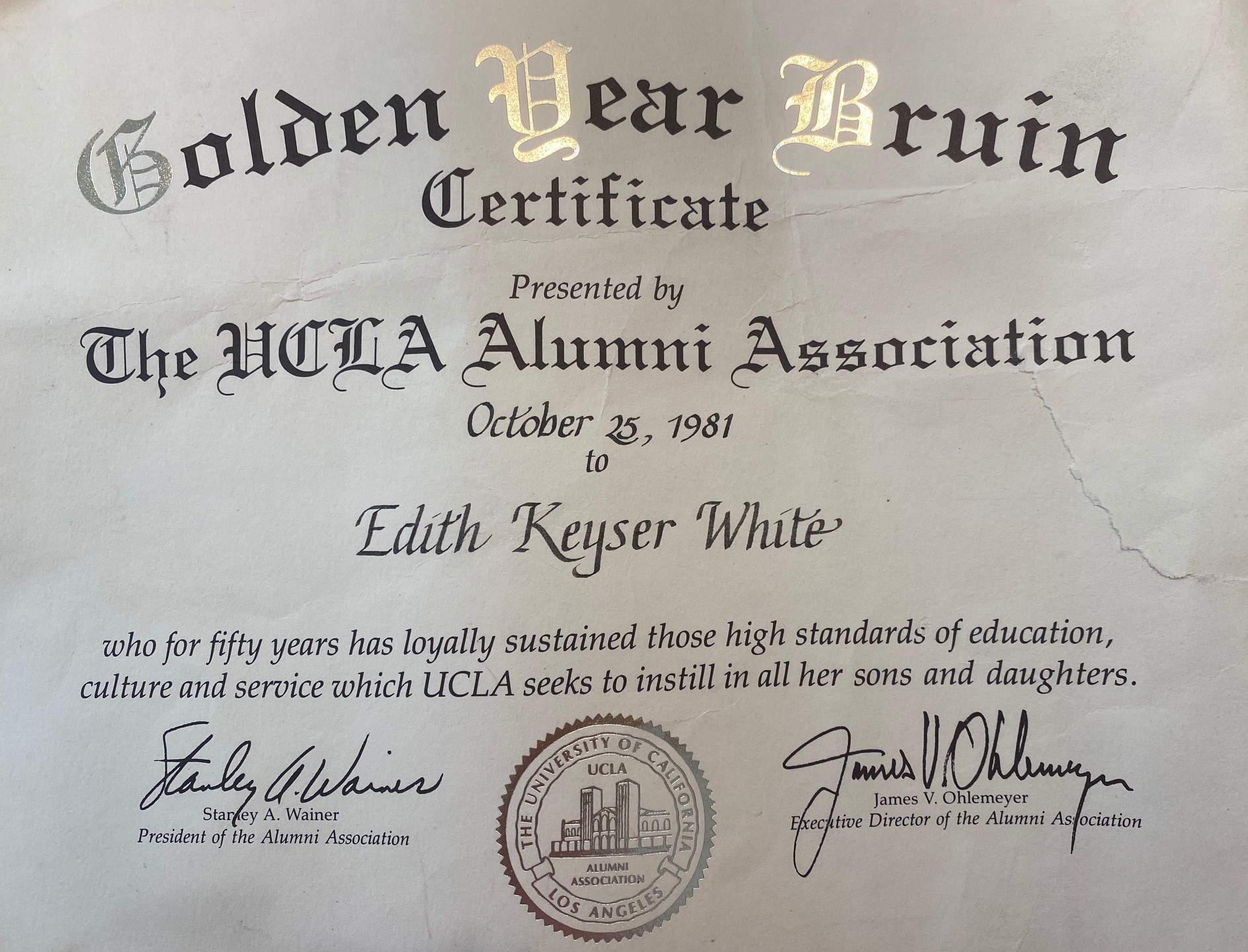

Edith’s story was related by her daughter, Teresa White Riddle ’68, M.Ed. ’76, the second Bruin in her family, after her mother, to live to celebrate a golden anniversary as a UCLA grad. Teresa’s sister, Alice White Parrish ’69, passed away in 2017, two years short of that milestone.

But it’s much more than longevity that distinguishes this family of Bruins. For they are the embodiment of the True Bruin Spirit that guides, encourages and motivates us to overcome, achieve and, where possible, give back.

Edith was born in 1909 in Mobile, Ala., the baby of the family and the only girl among four children. The family moved to Los Angeles when she was 10 and, using a friend’s address, Edith eventually attended Los Angeles High School. After starting UCLA at its original location on Vermont Ave. and graduating in Westwood, she had wanted to work in education, but another barrier prevented that – at least in her adopted hometown.

“My mother could not work for L.A. City schools because they did not hire black people as secondary teachers,” Teresa said. “So she went to work as a social worker for the County of Los Angeles. When World War II came, the color barrier was lifted and she went to work for L.A. Unified - she was a truant officer for about 20 years.”

Edith, her husband, Harry Clifton (Cliff) White, Sr., a mail carrier for U.S. Postal Service, and their three children, Teresa, Alice and their younger brother, Harry, moved from 41st Street to Silverlake in 1958. It wasn’t the easiest of transitions.

“My mother had her cousin, who was very fair, buy the lot, because she was worried that they would not sell to a Negro. So he bought it and quitclaimed it to her. We built the house and we moved in on a Monday. The following weekend, my father was out shoveling dirt and the man next door came over and asked, ‘Have you moved in here?’ My father said, ‘Yes, we have – hello.’ And the man said, ‘Well, I don’t live next door to n*****s.’ And my father said, ‘Well, I guess you’ll have to move, because we’re not going any place.’ And he did – he and his wife moved – they would not live next to us.”

This type of attitude was, of course, not restricted to Silverlake, nor was it applied to people of any particular social class – popular singer Nat King Cole faced similar hostility from neighbors when he wanted to move to upscale Hancock Park. But another constant in Teresa’s childhood was more positive: her mother’s ongoing love for UCLA and her desire for her children to follow in her footsteps as Bruins. In fact, it was more than a desire; it was practically a requirement.

“She programmed us to go to UCLA,” Teresa said. “It’s not like we had a choice! UCLA used to have an open house every fall and she would take us and we would walk around and she would say, ‘This is where your aunt and I used to eat lunch’ or ‘this is where I had my history class’ or ‘Dean Rieber’s office was over here.’ So we went to UCLA. I loved it.”

At the end of her sophomore year, Teresa decided she wanted to live on campus. A family trip to Europe – their second – was planned for the summer, but Teresa said, “I don’t want to go to Europe again. If you will just give me the airfare you were going to pay for me, I will work to earn the rest of the money and I want to move to the dorm.” Edith agreed and Alice, a year behind Teresa, decided she also wanted to live on campus. Both of them stayed home that summer, worked at the YMCA to earn some money, and, the next fall, Teresa moved into Dykstra Hall and Alice moved into Rieber Hall, named after the dean of the College of Letters and Sciences when her mother was a student.

“I’m a very social person and I didn’t want to just know my friends from Marshall High School,” Teresa explained. “I wanted to meet other people. And I met three women in the dorm who are my closest friends in the world.”

Even Teresa’s move to “The Hill” in 1966 was not without incident. “When I moved into Dykstra, the woman they assigned as my roommate told me she could not live with a Negro. So she went to whomever – or her parents did – and the next thing I knew, she was moving out. But the University of California would not give her another room. They told her that if she couldn’t live with where she was assigned, she would have to leave the dorm.”

Teresa moved a little higher on the hill the next year.

“Near the end of my junior year, living in the dorm, I saw an ad in the Daily Bruin that they were looking for ‘house advisors,’ so I applied and I was the first African American person ever to be house advisor. At the interview, the lady said to me, ‘Your grades aren’t excellent; do you think you’re going to be able to be a house advisor and do your school work?’ And I said, ‘Yes, I think I can manage that.’ I mean, it wasn’t like it was a full-time job - I wasn’t scrubbing floors. So I was a house advisor on sixth floor, women’s wing, of Hedrick Hall during my senior year. I was responsible for keeping the noise down, making sure no men were coming, except at the times when men were allowed, etc. Once I had to coax a girl out of her closet during fire drill, because she didn’t want to be seen with her hair in a bad state. I loved it; it was a wonderful year.”

While Teresa did participate in some of the student activism of the ‘60s – she was part of a sit-in at Murphy Hall, she wore a black arm band at graduation to protest the Vietnam War – she never experienced any institutional or systemic discrimination herself. She says that she always felt very comfortable on campus, inside and outside of the classroom.

“It was not threatening. I had African American and white friends, Jewish. My sister met a number of African American women who remained her friends until the day she died – they’re still my friends and we still talk about our days at UCLA.

“I think it was very fair. Because I had gone to junior high and high school at white schools, UCLA did not seem different for me. Perhaps if I had come from an all-Black school, it would have been different, but, for me, it was pretty much just a continuation of what I had done before. And I don’t think there was ever a professor who made an example of me or gave me a bad grade because of my ethnicity – I don’t feel that that really happened.”

Perhaps this attitude was, at least in part, passed on from her mother. “My mother tried never to stress with her children racial injustice directed towards us – we talked about all the political stuff; there was Martin Luther King and the march on Washington and all that, but with her own children, she tried not to say, ‘You got that grade because you’re black or that happened because you’re a Negro.’”

Edith’s influence was also evident in her oldest daughter’s career path. A political science major as an undergraduate, Teresa received her teaching credential at UCLA in 1969 and earned her M.Ed. in school administration. She went to work for the L.A. Unified School District for 34 years, taught U.S. government and Black history, and then became an administrator – an assistant principal and, finally, principal at Paul Revere Middle School on Sunset Blvd. in Brentwood. “The school was 50 years old, and I was the first woman and the first person of color to be the principal,” she noted. Her sister Alice also worked for LAUSD – coincidentally, also for 34 years.

There are some non-UCLA alumni in Teresa’s family: her daughter, Dr. Nicole Teresa Riddle, graduated from Tufts University (although she might qualify as an honorary Bruin, since she did attend day camp and a special class for high school students at UCLA). Teresa’s brother, Harry White, who passed away from AIDS in 1995, worked for the Orange County Public Defender’s Office and was general counsel for the University of California. He had scored a 1600 on his SAT, graduated from Yale in 1973 and from Harvard Law in 1976.

Though there have clearly been other educational institutions and many locations of significance in her family’s history, Teresa sums up her feelings for the university attended by her mother, her sister and herself by simply saying, “UCLA is the most important place in my life.”

We’re celebrating multi-generational Bruin families as a part of UCLA’s history. Are you part of a multi-generational Bruin family? If so, send your image and story to community@alumni.ucla.edu for a chance to be featured. #MultiGenBruins